Let's Learn Music Theory 05: Cadences and Non-Chord Tones

by FiniteZer0 (Apr 28, 2012)

Introduction

In this lesson we will apply our knowledge of chords to create a sense of finality, this phenomenon is known as a cadence. In addition to ending a musical thought, we will learn how to embellish our chords to create a more interesting sound rather than just using chord tones. Along with cadences, we will apply some of the analysis techniques we learned in lesson four to understanding harmonic function. We will also be viewing examples which will help us create an understanding of four part writing to help us visualize examples for when we tackle it.

Harmonic Cadence

To understand the concept of harmonic cadence, one must understand the phrase.

Phrase: A musical thought that ends in a cadence.

Phrases are the culmination of harmony, melody, and rhythm. In this lesson we will primarily focus on the harmonic and rhythmic aspects of cadence; we will cover the melodic aspect in the next lesson.

Now to establish the harmonic cadence.

Harmonic Cadence: The musical punctuation that ends phrase and/or section of a piece. It can also indicate that a a continuation of a musical thought. Most cadences end with a V or a I chord with the dominant chord usually written as V7.

Here is the list of possible cadence conclusions:

Authentic Cadence

Half Cadence

Plagal Cadence

Deceptive Cadence

Now we will go into detail about how to form each cadence and what they can look like.

The Authentic Cadence

The authentic cadence is considered the strongest cadence for it tells the listener the thought has ended. To form the authentic cadence, one simply needs to progress from the V to the I chord (yes, V to i exists even in minor; composers rarely use v to i); there is one exception to the rule, which we will cover. The reason why V to I creates the finality is because of the "ti-do" relationship, that is the leading-tone naturally leads back to the tonic, and the ti is present in the V chord (sol-ti-re) whereas in a v te (pronounced tay) replaces ti (sol-te-re), creating a weaker conclusion.

Now there are two types of Authentic Cadences perfect and imperfect.

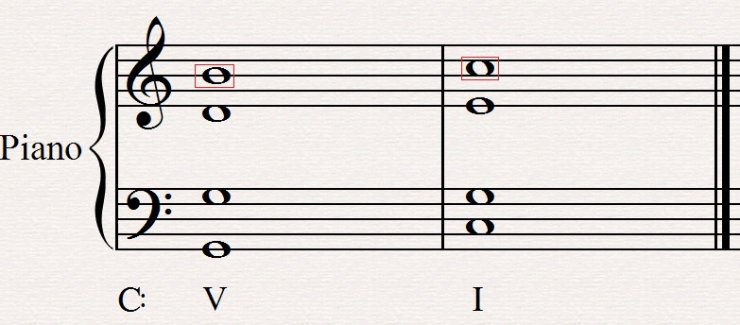

A perfect Authentic Cadence occurs when:

[dot]Both chords must be in root position

[dot]In the I chord, the root must appear in both the Soprano and the Bass.

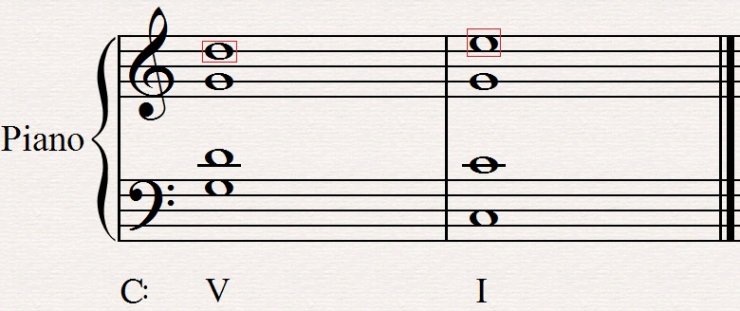

Now since a perfect Authentic Cadence exists, an imperfect authentic cadence must as well. An imperfect authentic cadence is slightly weaker than a perfect one and you can create it in any of these scenarios.

[dot]The highest sounding note in tonic is not the root; it can be a third or a fifth

[dot]The vii0 substitutes for the V creating a vii0 to I or vii0 to i.

[dot]Either or both chords (V or I) are inverted.

The Half Cadence

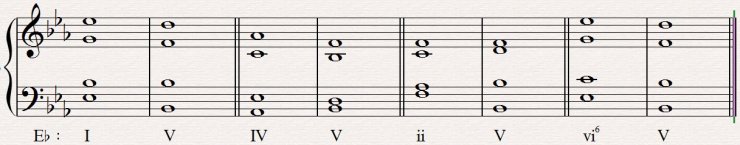

To form a half cadence, the final chord must be the V chord. This leads to a large number of possibilities but the most common half cadences are as follows: I-V, IV-V, ii-V, and vi6-V (Phyrigian half cadence).

The Plagal Cadence

The plagal cadence consists of one progression, which is IV-I in major keys and iv-i in minor. In very rare cases a ii6-I occurs.

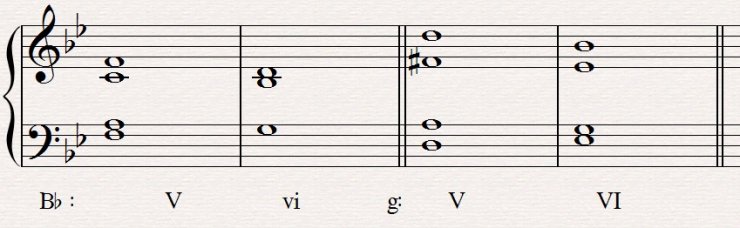

The Deceptive Cadence

To form a deceptive cadence have the penultimate chord be V but do not resolve back to I; most composers use V-vi (major) or V-VI (minor).

Cadences in Relation to Rhythm

Composers frequently signify an approaching cadence via rhythm, this phenomenon is known as a rhythmic cadence. A rhythmic cadence regularly end on longer notes or are proceeded by rests. In the next example, clap the rhythm before you listen to the piece to see if you can spot the cadences.

(Example 5.7;include midi)

Now that we have gained a basic understanding of cadences we now can move onto ways to spice up our chord progressions with the use of harmonic tones.

Non-Chord Tones

To understand a nonharmonic tone (non-chord tone), you first need to understand harmonic tones, which are as follows: root, third, or fifth. A nonharmonic tone is a tone that is played with a chord but not a part of that chord; by inputting nonharmonic tones, you create a more dissonant sound, which creates a more interesting progression. Dissonant intervals are created at the second, fourth, or seventh. Nonharmonic tones usually follow this formula:

Preceding Tone Chord Tone

Nonharmonic Tone Nonchord Tone

Following Tone Chord Tone

Now I will give you a list of harmonic tones that you need to memorize:

Name Abbreviation

Passing Tone PT

Neighboring Tone NT

Escape Tone ET

Appoggiatura APP

Suspension SUS

Retardation RET

Anticipation ANT

Pedal Tone PT

Changing Tone CT

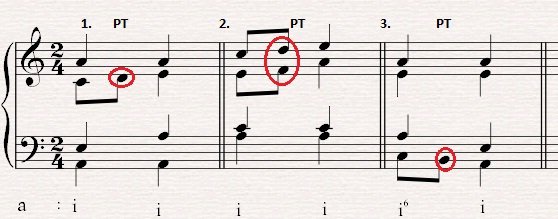

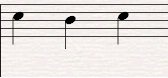

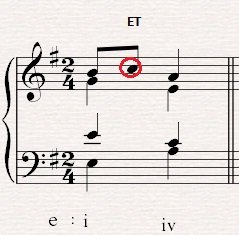

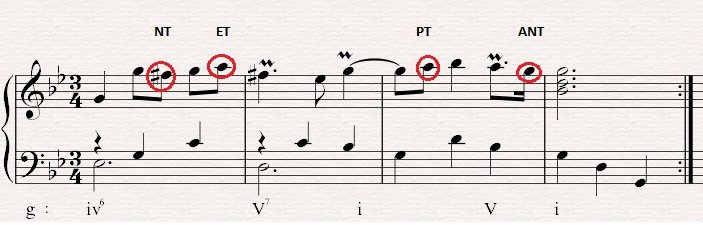

(Figure 5.8)

When analyzing music, it is best to circle the nonharmonic tones and label it to gain a better understanding of the piece.

When dealing with nonharmonic tones, two terms you must understand are accented and unaccented. In order to accent a nonharmonic tone, it must start on a chord; not under an accent mark, and to create an unaccented nonharmonic tone, it must not start on a chord.

(Example 5.9)

Now let's go over each of the nonharmonic tones so that we are able to identify them.

Unaccented Nonharmonic Tones

The most common unaccented nonharmonic tones are as follows: passing tone, neighboring tone, escape tone, and anticipation.

Passing Tone

To form the Passing Tone, simply ascend or descend the staff in a stepwise motion (Space-Line-Space or Line-Space-Line).

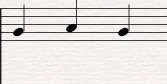

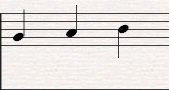

This is the ascending Basic Linear Figure for the Passing Tone:

This is the descending Basic Linear Figure for the Passing Tone:

The Passing Tone is unique for it is both unaccented and accented. In an unaccented passing tone follows a basic linear figure, meaning it usually flows in one direction either ascending or descending. Sometimes double passing tones may appear, but not often.

Here are some of the ways you can do a passing tone.

Neighboring Tone

To form the Neighboring Tone, simply ascend or descend in a stepwise motion then return back to the original note (Line-Space-Line or Space-Line-Space).

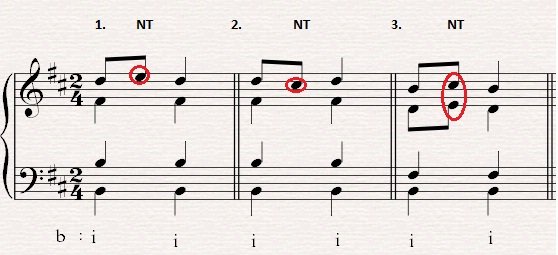

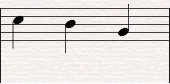

Ascending:

Descending

Like the passing tone, the unaccented neighboring tone can have double neighboring tones together.

Escape Tone

Escape tones usually consist of a step upward followed by a skip downward by a third.

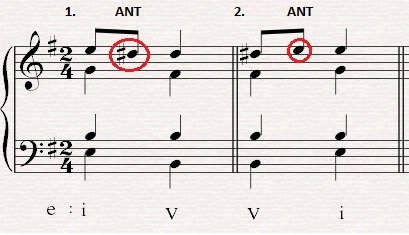

Anticipation

To create this unaccented tone, simply write the note of the next chord (usually a step down or up) before the chord.

Ascending:

Descending:

Here is an example by Handel in which he uses all of the nonharmonic tones we just learned!

Play MIDI

Accented Nonharmonic Tones

Here are the accented nonharmonic tones Passing Tone, Neighboring Tone, Suspension, Retardation, and Appogiatura. All of these occur on the chord rather than between it as with the unaccented nonharmonic tones.

Accented Passing Tone

As with the unaccented passing tone, it is either an ascending or descending linear figure; however, the only difference is nonharmonic tone occurs on the chord rather than between it.

(Example 5.13)

Accented Neighboring Tone

Similar to the unaccented neighboring tone, only like the accented passing tone, the nonharmonic tone occurs on the chord rather than during (read: between) the chord.

(Eample 5.14)

Suspension

This nonharmonic tone will require a bit of discussion in order to understand it. It comes in three parts preparation, suspension, and resolution; another way to remember it is consonance, dissonance, consonance.

(Figure 5.15)

There are four major types of suspensions 9-8, 7-6, 4-3, and 3-2, all of which are named after the intervals which happen to form when creating a suspension.

(Figure 5.16)

Remember, suspensions 9-8, 7-6, and 4-3 usually occur in the upper voices (Tenor, Alto, and Soprano) whereas 3-2 usually appears in the bass.

(Figure 5.17)

Retardation

Retardation has a very similar figure to Suspension, however the main distinction between the two is the resolution. Moving a step upwards resolves Retardation whereas moving a step downwards resolves Suspension.

(5.18)

Appogiatura

To form an Appogiatura is to skip upwards and then resolve a step downwards. The key to remembering how to create an appogiatura is to apologize for skipping.

(Figure 5.20)

Unique Nonharmonic Tones

The next two nonharmonic tones are unique in the sense that the require a minimum of three tones to create the nonharmonic sound, whereas before we dealt with figures that consisted of only thee tones.

Pedal Tone

Forming a Pedal Tone simply requires the Bass to repeat its note over a span of several chords creating a pattern of consonance and dissonance.

(Figure 5.21)

Changing Tones

To create a changing tone, you must use two successive nonharmonic tones in a row. The first tone must take a step away from the chord and the second one must skip away from the first nonharmonic tone, and lastly it must resolve back into a chord.

(Figure 5.22)

Successive Passing Tones

Sometimes using one passing tone is not enough, in which this technique must be used. Simply add another passing tone to create two nonharmonic passing tones which resolve into a chord.

(Figure 5.23)

Homework

Assignment 5.1

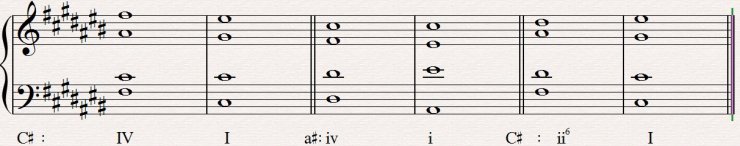

Annotate the following using Roman Numeral Analysis

[dot]Harmonic Function

[dot]Nonharmonic Tones

[dot]Cadence

Since the picture would be too small for you to properly annotate click on this link and it will take you to the PDF which will give you plenty of room to analyze this piece.

Assignment 5.2

Annotate the following using Roman Numeral Analysis

[dot]Harmonic Function

[dot]Nonharmonic Tones

[dot]Cadence

Since the picture would be too small for you to properly annotate click on this link and it will take you to the PDF which will give you plenty of room to analyze this piece.

(Hint: For repeated or arpeggiated chord, you do not need to rewrite the harmonic function; you can either leave it blank or use a - to indicate it.)