Modulation - A Comprehensive Walk-Through

by FiniteZer0 (Feb 09, 2012)

Modulation - A Comprehensive Walk-Through

Introduction

It has remained an unwritten rule that it is unaesthetic to remain in single key throughout the duration of a piece. So it is necessary to transition from one key to another whether it be abruptly or gradually. To accomplish a change of key is to manipulate the tonal center of a piece. Essentially, one wants the espousal of a different tone to which all other tones are created. For example, let's use the C major triad.

E|----

B|----

G|--0-

D|--2-

A|--3-

E|----

C: I

F: V

G: IV

A: III

E: IV

D: VII (descending minor)

C#: V of III

Eb: V of II

E: V of the Neapolitan Sixth

The foundation behind modulation is the ambiguity of a single chord. As demonstrated with the C major triad, a chord can be translated into several different keys.

It is important to note there are three mental steps that must be crossed when performing a modulation. First, the tonality must be made clear to the listener. Second, the composer at any given point can create a new tonal center (go from C major to D major). Third, the new tonal center is understood by the listener and he accepts it.

The Initial Key

The first key must be established and observed by the listener. It is important to note that it is not necessary to use the tonic chord for the initial key to be established; however, it is necessary for the dominant chord to be established and observed. It should be noted that frequent overuse of modal degrees and harmonies may result in a whole phrase being heard in the secondary key, especially if the second key is strongly established. If a modulation does not appear in the first phrase it carries less responsibility to establish the first key, provided that the key is of the preceding cadence.

The Pivot Chord

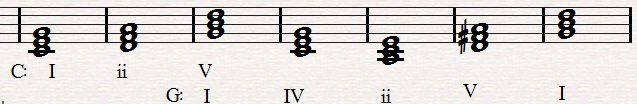

The second phase of modulation necessitates the choice of a chord which will be subject to the manipulation of the tonal view of the piece. In layman's terms, pick a chord that is common between two different keys to perform a modulation. For example

E|----|----|----|----|----|----|----|

B|----|----|--3-|----|----|----|--3-|

G|--0-|--2-|--4-|--0-|----|--2-|--4-|

D|--2-|--3-|--5-|--2-|--2-|--4-|--5-|

A|--3-|--5-|----|--3-|--3-|--5-|----|

E|----|----|----|----|--5-|----|----|

Take note of the smooth transition from C major to G major. It should be noted that the pivot chord may not be the V of the second key. The sounding of the V will be used later to establish the new key. In essence, use of the V will make the tonal center realized. The pivot chord must precede the V of the second key like the example provided above.

The New Key

The establishment of the new key is realized via the cadence that ends the phrase. It should be noted that it is possible to construct a strong progression in the new key before the cadence is completed.

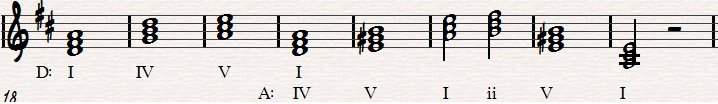

E|------|------|--0---|------|--0--2-|------|-------|

B|------|--3---|--2---|--1---|--2--3-|--1---|-------|

G|--2---|--4---|--2---|--2---|--2--4-|--2---|-------|

D|--4---|--5---|------|--2---|-------|--2---|--2----|

A|--5---|------|------|------|-------|------|--4----|

E|------|------|------|------|-------|------|--5----|

This progression is a modulation up a perfect fifth, or it creates a new tonal center around the dominant chord. The key of D major is irrefutable with the progression I-IV-V-I; since the tonic chord (I) D is the sub-dominant chord (IV) in A, the IV becomes the pivot chord to introduce the V in the new key. The progression of IV-V in A creates a strong tonal cadence. The authentic cadence is further augmented by the ii preceding the V-I.

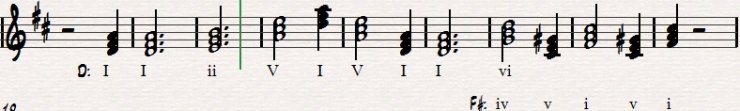

E|------|------|------|--0--5-|--0----|-------|-------|-------|------|

B|------|------|--0---|--2--7-|--2----|-------|-------|-------|------|

G|--2---|--2---|--0---|--2--7-|--2--2-|--2----|-----1-|--2--1-|--2---|

D|--4---|--4---|--2---|-------|-----4-|--4----|--4--4-|--2--4-|--2---|

A|--5---|--5---|------|-------|-----5-|--5----|--5--4-|--4--4-|--4---|

E|------|------|------|-------|-------|-------|--7----|-------|------|

In this example, the progression moves up a major third. The progression ii-V-I affirms the key of D. The sub-mediant (vi) becomes the pivot chord in the major mode and becomes the sub-dominant (iv) in the minor mode F-sharp; it is then affirmed in the progression iv-v-i.

Related Keys

All keys are related, end of story. The question is, however, to what degree are the keys related? The term "related keys" always means the keys which are closely related. The relationship is established by two aspects: how many common tones are there? are the tones in the same "family"?

Let's look at a few scales now.

G A B C D E F# G

C D E F G A B C

D E F# G A B C# D

E F# G A B C D E

A B C D E F G A

B C# D E F# G A B

First organize these tones by the amount of common tones they have in common. That would give us a result like this:

C D E F G A B C

A B C D E F G A

G A B C D E F# G

E F# G A B C D E

D E F# G A B C# D

B C# D E F# G A B

Now indirectly, we have also organized these tones by their relative majors and minors (C major and A minor; G major and E minor; D major and B minor). All these tones use the same key signature.

Now there is one more form of modulation and that is enharmonic modulation, and alas I have not yet come to understanding how this form of modulation works. Here is an excerpt from Wikipedia which describes the phenomenon:

An enharmonic modulation takes place when one treats a chord as if it were spelled enharmonically as a functional chord in the destination key, and then proceeds in the destination key. There are two main types of enharmonic modulations: dominant seventh/augmented sixth, and diminished seventh -- by respelling the notes, any dominant seventh can be reinterpreted as a German or Italian sixth (depending on whether or not the fifth is present), and any diminished seventh chord can be respelled in multiple other ways to form other diminished seventh chords. By combining the diminished seventh with a dominant seventh and/or augmented sixth, changing only one pivot note at a time, it is possible to modulate quite smoothly from any key to any other in at most three chords, no matter how distant the starting and ending keys; however, the effect is easily overworked.

(Examples: C-E-G-B♭, a dominant 7th, becomes C-E-G-A♯, a German sixth. C♯-E-G-B♭, a C♯ diminished seventh, can also be spelled as E-G-B♭-D♭, an E diminished seventh, G-B♭-D♭-F♭, a G diminished seventh, and B♭-D♭-F♭-A♭♭, a B♭ diminished seventh. Combining the diminished 7th with the dominant 7th/aug.6th: starting again from C♯ diminished seventh, the progression C♯-E-G-B♭, C♯-E-G-A (dom.7th), D-F♯-A takes us to the key of D major; C♯-E-G-B♭, C-E-G-B♭ (dom.7th), C-F-A, to F major; but exactly the same progression enharmonically C♯-E-G-B♭, C-E-G-B♭(dom.7th)=C-E-G-A♯(aug.6th), B-D♯-F♯-B takes us somewhat unexpectedly to B major; C♯-E-G-B♭, C♯-E♭-G-B♭=D♭-E♭-G-B♭(dom.7th), C-E♭-A♭ to A♭ major; etc. )

(Examples: C-E-G-B♭, a dominant 7th, becomes C-E-G-A♯, a German sixth. C♯-E-G-B♭, a C♯ diminished seventh, can also be spelled as E-G-B♭-D♭, an E diminished seventh, G-B♭-D♭-F♭, a G diminished seventh, and B♭-D♭-F♭-A♭♭, a B♭ diminished seventh. Combining the diminished 7th with the dominant 7th/aug.6th: starting again from C♯ diminished seventh, the progression C♯-E-G-B♭, C♯-E-G-A (dom.7th), D-F♯-A takes us to the key of D major; C♯-E-G-B♭, C-E-G-B♭ (dom.7th), C-F-A, to F major; but exactly the same progression enharmonically C♯-E-G-B♭, C-E-G-B♭(dom.7th)=C-E-G-A♯(aug.6th), B-D♯-F♯-B takes us somewhat unexpectedly to B major; C♯-E-G-B♭, C♯-E♭-G-B♭=D♭-E♭-G-B♭(dom.7th), C-E♭-A♭ to A♭ major; etc. )